Split-Dollar Arrangements – The Structure

What are the Key Components in a Split-Dollar Arrangement?

While there are numerous variations in split-dollar arrangements, their structure and documentation depends primarily on three major factors:

- The ownership of the life insurance policy (“policy”),

- The split of premium payments on the policy, and

- The division of policy equity.

Notes

- Other, less common ownership structures include (1) the unsecured method and (2) the co-ownership method. The unsecured method involves a purely contractual arrangement between the parties where the policy is not used to secure the business’ repayment right. This approach may minimize some problems associated with the traditional methods (such as the appearance of a loan), but the income tax treatment of the benefits provided to the employee are uncertain. The co-ownership method divides ownership of both the policy cash value and death benefit between the business and the employee (or other third party owner), which attempts to address the potential taxation of the policy equity to the employee. The income tax impact of the arrangement is uncertain, however, and the arrangement is not conducive to managing the estate tax exposure of the insured if he or she is the controlling shareholder of the business. Both methods are deemed split-dollar arrangements for purposes of the final regulations. For a more detailed discussion of these alternate documentation arrangements, see Brody, Richey, and Baier, 386-4th BNA T.M Portfolio, Insurance-Related Compensation, Art. IV.B.2.

- Note that whenever a business entity owns a life insurance policy, including under a policy subject to the terms of a split-dollar arrangement, the potential application of IRC §101(j) should be reviewed. IRC §101(j) provides for the income taxation of death benefits paid to owners of certain “employer-owned life insurance” contracts insuring the life of a business’ employee or other key individuals. Tax can be avoided in most situations if certain notice and consent requirements are met prior to contract issuance. IRC §101(j) does not apply to policies issued prior to April 18, 2006 or received in an IRC §1035 exchange for a policy issued prior to that date unless there is a material increase in the death benefit or other material change to the contract.

- Federal and state securities laws can impact split-dollar arrangements involving publicly-traded companies, with potentially serious consequences. In particular, a split-dollar arrangement resembling a loan transaction may cause issues under the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002 (“SOX”) due to its prohibition on personal loans to directors and covered executives. Note that although SOX does not technically apply to nonprofit organizations, many of these organizations have voluntarily adopted certain SOX-like provisions, including prohibitions on personal loans to directors and executives. If working with a nonprofit, be sure to review the organizations policies and whether a split-dollar arrangement with an organization’s director or executive would be in compliance.

- In some cases, since the business is the only party invested in the policy, a non-contributory arrangement may require the insured to personally reimburse the business for premiums paid but not recovered due to early termination of the insured’s employment, although the insured will likely view this as an undesirable financial burden.

- For a more detailed discussion of possible premium split arrangements, see Zaritsky & Leimberg, Tax Planning With Life Insurance: Analysis With Forms, §6.05 [1][a] and [b] (Thomson Reuters/WG&L, 2d Ed. 1998, with updates through May 2013)(online version accessed on Checkpoint (www.checkpoint.riag.com); Brody, Richey, and Baier, 386-4th T.M., Insurance-Related Compensation, Art. VI.B.1.

- See Zaritsky & Leimberg, Tax Planning with Life Insurance: Analysis with Forms, §6.05 [1][b][i], supra, note 5.

- Confusingly, a reference to a “contributory plan” may specifically mean this type of economic benefit offset plan. Such plans also were formerly known as “P.S. 58 offset” or “P.S. 58 contribution” arrangements, because the value of the taxable benefit provided to the employee (i.e., the annual cost of life insurance coverage) was based on the P.S. 58 mortality tables originally published in 1946. In 2001, the IRS replaced the P.S. 58 tables with Table 2001 (see Notices 2001-10, 2001-1 CB 459, and 2002-8, 2002-1 CB 398).

- See, David Houston & Maggie Mitchell, “Skeletons in the Closet: What to Do with “Grandfathered” Split-Dollar Arrangements,” The AALU Quarterly, Spring 2012.

- Id. Some discussions of split-dollar arrangements will reference “equity” as the difference between the premiums paid and the policy’s cash value. See e.g., David Houston & Maggie Mitchell, “Skeletons in the Closet: What to Do with “Grandfathered” Split-Dollar Arrangements, supra note 9 (“Equity refers to the [policy] cash value in excess of [total] premiums paid.”); Kathryn G. Henkel, Estate Planning and Wealth Preservation: Strategies and Solutions, §2.06 (Thomson Reuters/WG&L 1997, with updates through November 2013) (online version accessed on Checkpoint (www.checkpoint.riag.com) February 2014) (“An equity split-dollar arrangement generally involves an arrangement where the term portion owner also receives benefits attributable to investment performance of the policy (e.g., cash surrender value in excess of premiums paid).”); William P. Streng & Mickey R. Davis, Retirement Planning: Tax and Financial Strategies, §17.02[2][c][iv] (ThomsonReuters/WG&L, 2013 ed., updated September 2013 and visited February 2014) (At the “crossover point,” when the investment returns on the assets within the insurance policy overcome the insurance charges, commissions, and administration charges that initially eroded the cash value, the policy cash value exceeds the amount of premiums paid, creating “equity” in the contract.”).See e.g., Charles L. Ratner and Stephan R. Leimberg, “A Planner’s Guide to Split-Dollar After the Final Regulations,” Estate Planning Journal (WG&L), January 2004 (In equity split dollar, “the employer is usually repaid the lesser of (1) the total premiums it advanced or (2) the policy’s cash value. Any cash value greater than the employer’s share is the equity, which is, from inception, nonforfeitable by the employee but physically passes to the employee when the arrangement is terminated.”); Lawrence Brody and Michael D. Weinberg, “The Side Fund Split-Dollar Solution: A New Technique for Split-Dollar,” note 11, Estate Planning Journal (WG&L), January 2006 (“‘Equity’ means cash value in excess of the amount necessary to repay the corporation or the grantor for their premium outlays.”). See also TAM 9604001 (where, in an effort to currently tax the build-up of policy “equity” under a grandfathered split-dollar arrangement to the insured, the IRS refers to the portion potentially taxable to the insured as “any cash surrender buildup in the policies that exceeds the amount that is returnable to [business] when the arrangement is discontinued”) and Notice 2002-8, Sec. IV.1. (where, in setting forth certain safe harbors for the taxation of grandfathered split-dollar arrangements, the IRS states that “For split-dollar life insurance arrangements entered into before the date of publication of final regulations, the Service will not treat a service recipient as having made a transfer of a portion of the cash surrender value of a life insurance contract to a service provider for purposes of section 83 solely because the interest or other earnings credited to the cash surrender value of the contract cause the cash surrender value to exceed the portion thereof payable to the service recipient.”).See e.g., Zaritsky & Leimberg, Tax Planning With Life Insurance: Analysis With Forms, §6.05[1][b][v], supra note 5 (“An equity split-dollar life insurance arrangement allows the employee to retain some or all of the excess of the cash surrender value above the amounts contributed by the employer.”); Lawrence Brody and Mary Ann Mancini, “Sophisticated Life Insurance Techniques,” ABA Section of Taxation Meeting, May 2011, Art. II.C.1.a. (“The taxation of policy equity in pre-Final Regulation arrangements – Defined: An arrangement where there are policy cash values in excess of cumulative premiums due back to the premium provider and the premium provider is only to get back its premiums, so that those excess cash values belong to the policy owner.”).See Regs. §1.61-22(a)(2) and (b)(3).

- Governed by Reg. §1.61-22.

- Governed by Reg. §1.7872-15.

- See Reg. §1.61-22(c)(1)(ii)(A)(1), which provides that an employer or service recipient is treated as the owner of a policy underlying a split-dollar arrangement that is entered into in connection with the performance of services, even if not the named owner of the policy, if, at all times, the only economic benefit that will be provided under the arrangement is current life insurance protection. In such a case, the economic benefit regime would apply, regardless of the ownership documentation method used.

Who Owns the Policy under a Split-Dollar Arrangement?

Depending on the ownership structure selected, the business, the insured employee or business owner (the “insured”), or a third party chosen by the insured (such as his or her irrevocable life insurance trust “ILIT”) is named as the owner on the policy. The most typical ownership structures are the endorsement method, where the business is the named policy owner, and the collateral assignment method, where the insured (or, commonly, his or her ILIT) is the designated policy owner.

Note that the final regulations may treat the business as the “deemed” policy owner for purposes of taxation of the split-dollar arrangement, even if the insured or the insured’s ILIT is actually named as owner on the policy (e.g., as in a non-equity split-dollar arrangement entered into between a business and employee, where the only benefit to the employee is current life insurance protection).

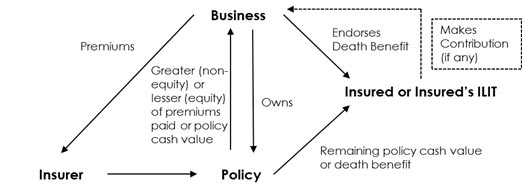

What is the Endorsement Method?

In an endorsement split-dollar arrangement, the business owns and is the beneficiary of the policy on the insured. The business files a policy endorsement with the issuing insurance carrier, endorsing the insured’s interest in the policy death benefit (i.e., amounts in excess of the premiums advanced by the business). The insured has the sole right to designate the beneficiary for the endorsed portion of the death benefit.

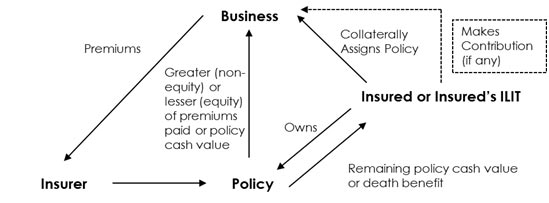

What is the Collateral Assignment Method?

Under a typical collateral assignment split-dollar arrangement, the insured (or, more commonly, the insured’s ILIT) owns the policy and designates the beneficiary. The business pays the agreed-upon portion of the premiums, as specified in the split-dollar arrangement. The insured files a collateral assignment of the policy with the issuing insurance carrier, securing the business’ right to repayment of its premium advances. The documentation under this method generally resembles a loan transaction.

Why Use the Endorsement Method vs. the Collateral Assignment Method?

The selection of the documentation method for a post-final split-dollar arrangement will depend in part on the tax consequences associated with naming as the policy owner either the business (the endorsement method) or the insured (the collateral assignment method), including whether the insured will have any right to policy equity. Certain practical considerations, however, also impact the selection of the documentation method.

Endorsement. The selection of an endorsement arrangement depends on whether the business wants greater control over the policy or the business intends to retain ownership of the policy at the arrangement’s termination (e.g., the business retains the policy as key person coverage when the arrangement terminates and uses the policy’s cash values and death proceeds to informally fund a nonqualified deferred compensation arrangement).

The endorsement method also is generally easy to implement and administer (as the business is primarily responsible for all aspects of the policy management). A business can more easily convert an existing business owned policy to a split-dollar arrangement by simply endorsing the death benefit to the insured (rather than transferring ownership of the contract).

Further, in some cases, a business may wish to avoid the appearance of a loan or debt transaction with the insured, for example, because of applicable securities laws or existing lending agreements that restrict corporate loans to employees (such as the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002 for public corporations). In these situations, a business may prefer the endorsement method, since the associated documentation looks less like a loan than the collateral assignment method.

Collateral Assignment. The collateral assignment method is generally employed when the insured (1) desires control over the policy and/or rights to the policy’s equity, (2) already owns the policy (or has a trust that owns the policy), and/or (3) will retain the policy (either directly or through his or her trust) upon termination of the arrangement. The collateral assignment method also can complement the insured’s estate tax planning, since the insured’s ILIT can directly apply for the policy and enter into the arrangement with the business, thereby keeping the policy death benefits out of the insured’s estate and away from both the insured’s and business’ creditors (unlike when the business owns the life insurance, which may allow the business’ creditors to reach the policy cash value).

Before the issuance of the final regulations, the collateral assignment method was the structure of choice for many grandfathered split-dollar arrangements, since it provided the insured with control over the policy and attempted to provide income tax-free access to the policy’s equity, which was expected to increase over time. Post-final split-dollar arrangement structured and taxed as loan arrangements generally will be documented as collateral assignment arrangements.

Who Pays the Policy Premiums under a Split-Dollar Arrangement?

With regard to premiums, split-dollar arrangements are either structured as (1) non-contributory plans (business pays all premiums) or (2) contributory plans (premiums are split between the business and insured).

Before the issuance of the final regulations, contributory plans not only allowed the insured to offset any imputed taxable income by an amount equal to the contribution made by the insured (or by the insured’s ILIT), but also, according to many, provided the insured (or his or her ILIT) with an income tax basis in the policy. Further, such contributions were income tax-neutral with regard to the business. The final regulations, however, changed the tax benefits associated with contributory plans, significantly impacting their use in structuring premium splits. Thus, while certain contributory plans will no longer make sense for new arrangements, they may still be found in certain grandfathered split-dollar arrangements.

What is a Non-Contributory Plan?

Under non-contributory plans (also called “employer pay all” plans), the split-dollar agreement requires the business to pay each annual premium on a policy, in full, for the duration of the arrangement, without any offsetting contributions from the insured. At the earlier of the insured’s death or other termination of the arrangement, the business recoups its premium advances (and any other amounts specified under the split-dollar agreement) from the policy death benefits or cash value, as applicable, with any excess passing to the insured or his or her designated beneficiary.

Practice Note: To offset the continual reduction in the employee’s portion of the death benefits due to the increase in the business’s premium reimbursement rights over time, the parties may agree to apply policy dividends to the purchase of one-year term insurance on the employee, which would supplement the total death benefit amount payable to the employee.

What Is a Contributory Plan?

A contributory plan is any split-dollar arrangement in which the insured (or his or her ILIT) contributes a portion of the premium payments. While there are numerous ways to divide the premium obligations between the business and the insured, common premium splits include the following:

- “Classic” Split: In a classic split, The business pays only that part of the annual premium equal to the annual increase in the policy’s cash value (or the entire premium, if lower), with the insured paying the balance.

- Example: X Co. and executive, E, enter into a contributory split-dollar arrangement to acquire a $1 million policy on E, with a classic premium split. The annual premium is $10,000. In the first year, the policy’s cash value increases by $1,500. X Co. pays $1,500 and E pays the balance of the premium, $8,500. In the next year, the cash value increases by $3,000. X Co. pays $3,000 and E pays $7,000 of the premium. When the policy’s cash value eventually increases by $10,000, X Co. pays the total premium.

This premium split minimizes the business’ exposure by trying to ensure that the policy always has sufficient cash value to reimburse the business’ premium advances. The insured, however, must initially bear a larger share of the premiums, until there is sufficient growth in the policy’s cash value. These initial contributions by the insured may exceed the actual income that would otherwise be taxable to the insured under the split-dollar arrangement, which typically is based on the annual cost of the term life insurance protection provided to the insured. The insured, however, cannot apply the excess contributions to offset future imputed income.

- Level-Outlay Plan: A level outlay plan is designed to minimize the initial premium burden to the insured from the classic split. Under this premium split, the parties specify a term during which the insured’s share of the premiums will remain the same. The insured’s share is determined by taking an average, over the specified term, of the portion of the annual premium equal to the value of the term life insurance protection provided on the insured’s life (the “term cost”), generally as determined under tables issued by the IRS (currently, Table 2001). The insured annually pays this average term cost during the leveling period, with the business covering the balance.

- Example: X Co. and executive, E, enter into a contributory split-dollar arrangement to acquire a $1 million policy on E, and agree to a 10-year level-outlay split. E is age 45 at the start, and the annual premium is $10,000. Based on Table 2001, the average annual term cost of $1 million of life insurance on E for 10 years is $2,360. For each of the first 10 years of the arrangement, E will pay $2,360 of the annual premium, with X Co. paying $7,640.

As compared to the classic-split, the level-outlay plan substantially lessens the premium share initially attributable to the insured, better matching the amount that would otherwise be taxable income to the insured. The plan, however, increases the business’ exposure, because there will be insufficient cash value in the early policy years to reimburse the business if the insured’s employment is terminated. As with a non-contributory plan, the business may require personal reimbursement from the insured for unrecovered premiums due to early termination.

- Contributory Offset or Zero Tax Split: In this premium split, the insured pays the portion of the premium equal to the value of the annual term cost. The business pays the balance of the annual premium, if any.

- Example: Assume the same facts as above, except the X Co. and E agree to a zero-tax premium split. In the first year, E is 45 years old. The Table 2001 cost per $1,000 of term life coverage for an individual, age 45, is $1.53, so E’s portion of the premium is $1,530. X Co. pays the remaining $8,470.

The insured’s contribution offsets the imputed taxable income equal to the term cost of the insurance coverage, which should minimize or eliminate the insured’s tax liability with regard to the arrangement.

What is “Bonus” Split-Dollar?

As a variation of the contributory offset plan, a business may bonus the amount of the insured’s tax liability with respect to the benefits under the split-dollar arrangement. Alternatively, the business may bonus both the tax liability and the tax on the bonus, eliminating all tax costs to the insured (sometimes called a “gross-up”).

What is Policy Equity?

A cash value life insurance product effectively has three parts: (1) cash value reflecting the total premiums paid; (2) gain in the contract, or cash value in excess of premiums paid, and (3) the death benefit in excess of the total cash value. While the term “equity” may refer generally to the gain portion of the contract,9.1 in the context of split-dollar arrangements, it also may refer specifically to the portion of the policy cash value in excess of the premiums advanced by the business under the arrangement.

Example: X Co. and executive, E, have an employer-pay-all split-dollar arrangement for a $1 million policy insuring E. The policy has a current cash value of $500,000. The business has advanced $300,000 in premiums. The policy “equity” is $200,000.

What is an Equity Split-Dollar Arrangement?

In an equity split-dollar arrangement, the insured has an interest in or right to some or all of the policy equity during and/or after termination of the arrangement, in addition to current life insurance protection.9.3 Although equity arrangements can be structured as endorsement split-dollar, they are more typically documented under the collateral assignment method.

In a typical equity split-dollar arrangement, the business’ reimbursement right is for the lesser of (1) the total premiums it paid or (2) the policy’s cash value. Any policy equity passes to the insured when the split-dollar arrangement terminates.

Example: Using the facts of the example above, if X Co. and E decide to terminate the arrangement, X Co. will be reimbursed for the $300,000 (the premiums it advanced), with E being entitled to the policy equity of $200,000.

Practice Note: Not all policies underlying equity split-dollar arrangements will have an equity component (for example, an underperforming policy may fail to develop any cash value over the premiums paid by the business).

What is a Non-Equity Arrangement?

As the converse to an equity arrangement, a non-equity split-dollar arrangement is one in which the business provides the insured solely with current life insurance protection, but no interest in the policy equity. The business pays the premiums and retains the right at termination of the split-dollar arrangement to receive the greater of (1) the total premiums paid or (2) the policy’s cash value. The insured has the right to designate the beneficiary for the portion of the death benefit in excess of the business’ interest in the policy.

Why Use an Equity Arrangement vs. a Non-Equity Arrangement?

The decision to use an equity or non-equity split-dollar arrangement will depend primarily on the purpose of the arrangement and the benefits the business desires to provide the insured. Where the business needs or wants to retain full access to, or control over, policy cash value, such as a form of golden handcuffs or to fund later retirement benefits for a key-employee, a non-equity arrangement will likely be used. If the business wants the insured to benefit and/or have current access to the growth within the policy, then an equity arrangement likely will make sense.

Economic Benefit and Loan Regime Split-Dollar

What Do References to Economic Benefit or Loan Regime Split-Dollar Mean?

The final regulations provide two mutually exclusive regimes to determine the taxation of post-regulation split-dollar arrangements: (1) the economic benefit regime, and (2) the loan regime. Which regime applies to the post-regulation arrangement depends on which party is the deemed owner of the policy for purposes of the final regulations — where the business is the deemed owner, the economic benefit regime generally applies, and when the insured (or his or her ILIT) is the deemed owner, the loan regime applies.

In most cases, the endorsement method will correspond to taxation under the economic benefit regime (because the business is the policy owner) and the collateral assignment method to taxation under the loan regime (because the insured or his or her ILIT is the policy owner). Under a special rule, however, a collateral assignment arrangement between a business and insured that only provides the insured with current life insurance protection (and no access to or rights to policy cash value) will still be governed by the economic benefit regime, even if the insured (or his or her ILIT) is named as the policy owner.

Example: X Co. and executive E’s ILIT enter into a split-dollar arrangement governed by the final regulations. X Co. owns the policy and, upon termination of the arrangement, is entitled to the greater of premiums advanced or the policy’s cash value. E’s ILIT is entitled to any death benefits paid under the policy in excess of the amounts owed to X Co. This is a non-equity endorsement, economic benefit arrangement. Consider, however, if E’s ILIT owned the policy, but with X Co. still entitled to receive, upon termination of the arrangement, the greater of the policy cash value or the premiums it advanced upon termination of the arrangement, secured by a collateral assignment of the policy. Even though documented as a collateral assignment arrangement with the policy owned by the insured’s ILIT, the arrangement would be taxed under the economic benefit regime, because the only value provided to the insured (though his or her ILIT) is current life insurance protection.

Practice Note: Although a post-regulation split-dollar arrangement will often be identified or referred to by the tax regime that applies to it, the documentation of the policy ownership under the post-regulation arrangement generally will still be based on the endorsement method or the collateral assignment method.